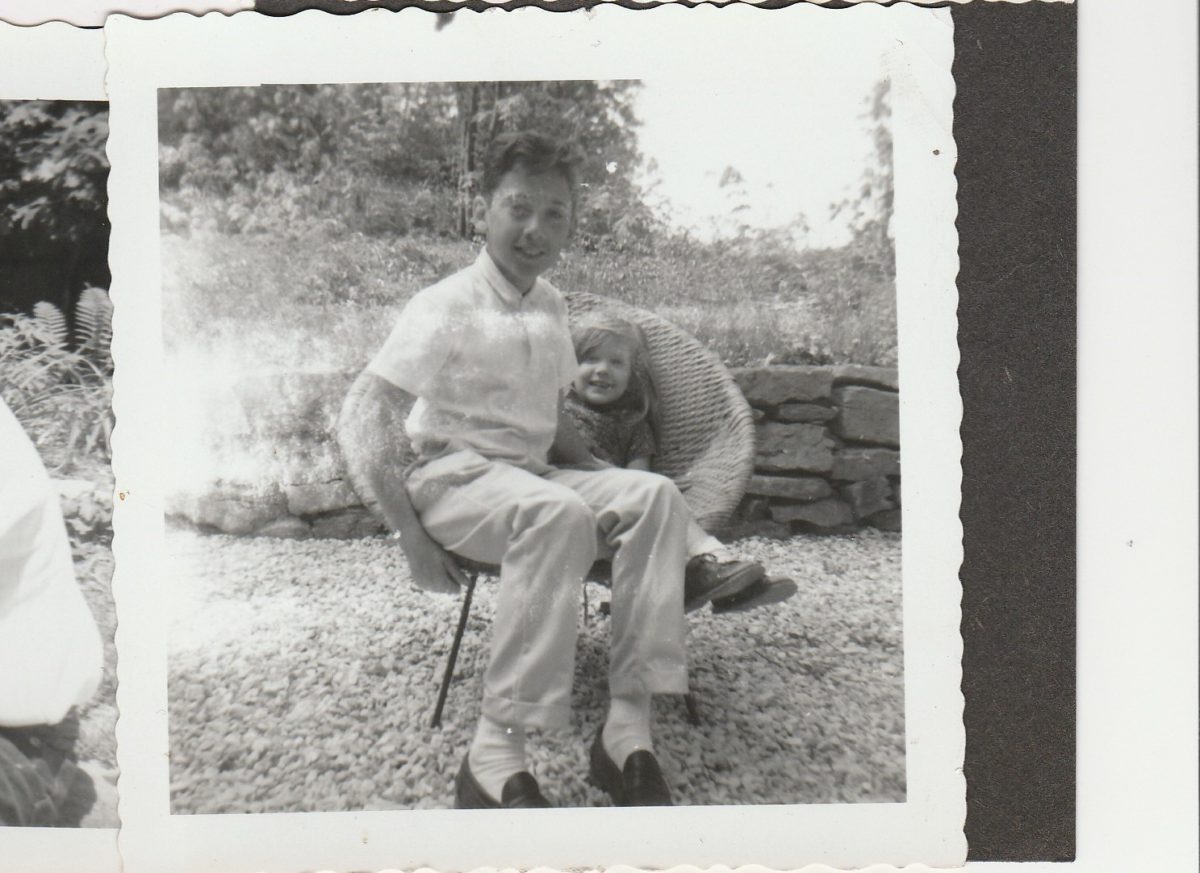

This post was written by Marc’s younger sister, Rebecca, shortly after he passed away:

My eldest brother Marc, 66, passed away on March 17th. I don’t need condolences, and I’ll tell you why.

Marc began showing symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia at the age of 18 – it was not his fault, or anyone else’s – just the crappy hand he was dealt. All the promise he had, as a brilliant scholar, poet, athlete and musician, was forever redefined.

He managed, in spite of his illness, not to get lost on the streets, like so many others; uncared for, feared, mocked and worst of all, passed by. He also managed, when he wasn’t tormented by paranoia or giving in to understandable bitterness, to have a wizened cow poke sense of humor, to be friendly to everyone he met, and most lasting, to write some heartbreakingly beautiful songs.

Like many people with his illness, he refused medication. He’d seen what it had done to friends of his who happened to be in the same boat, and the side effects scared him. The medicine would have made him better for us, but I’m not sure how much better the adjustment to his consciousness would have been for him, and the law didn’t allow anyone to force it on him anyway.

What the law also didn’t do was establish adequate resources for people with mental illness. Deinstitutionalization, beginning in the 1970s, did help a few people from being medicated against their will or from languishing in mental hospitals. It sounded like a good idea, but now many of our mentally ill are either homeless or incarcerated.

Marc refused any kind of medical care. In the last few years his health declined dramatically. My father, who turned 88 the day after Marc died, had been looking in on him weekly for many years, and never stopped urging him to get help.

Three days before he died, Dad and Francis, a man who had known Marc in better days, and who dropped like an angel from heaven earlier in the year to help, went to his apartment and called 911, hoping he would go willingly to the hospital. He refused, mustering, as he often did, enough strength and guile to make the emergency staff think he was “okay.” He even joked with them.

After speaking to Francis, and hearing the defeat in my dad’s voice, I dropped what I was doing and drove up to Vermont. I was afraid of what was coming, of seeing my brother suffering. He did suffer, greatly, but he also lived on his own terms and with tremendous courage. And even though the circumstances of his passing were traumatic, I felt blessed to be able to show him love on his journey out of this life.

In lieu of condolences, which are easy, I want to ask you to do something hard. Be aware of the suffering of the mentally ill, particularly the mentally ill who are homeless. Don’t be afraid of them, because they are rarely a danger to you. Know that they are much more than their mental illness – they have talents, opinions and passions, and they are worthy of respect and compassion.

Be very grateful for those who go into mental health social work, because it’s a tough job, and support the few politicians and legislators who care about the mentally ill. Let people like me talk to you about our loved ones, without judgement – know that we feel helpless, and guilty for having the life that our brothers, sisters, parents, or children might have wanted to have.

Be especially kind to the next person you meet who seems to be struggling with mental illness – because that poor soul could be my brother.